This product has been toppled (due to unavailability)

Click on the image above or here to see its replacement.

Preface

As always, we're looking at the Mountain Equipment Compressor Jacket from the point of view of long distance trekking over tough terrain.

Test subject: Chest 42", Waist 33", Height: 5ft 8"

Test item: 2014 version, size = Large

Kit Tests: Winter, Summer

Disclaimer: None required (item not provided by manufacturer)

Datasheet

| Outer fabric: Helium 30 (Mountain Equipment's proprietory material) | 100% |

| Synthetic Insulation: Primaloft One, now called Primaloft Gold (Body / Arms+Hood) | 60g / 40g |

| Weight (Size Large, 2014 model) | 380g |

| Product Sizing Reference: 42" Chest = | Large |

| Manufacturer RRP | £140.00 |

Scramble Review

Introduction: We want the world and we want it ...

Okay, so what do we want from a lightweight insulated jacket?

- To weigh less than 400g

- To be warm enough: 60g (or more) of high quality synthetic insulation (Primaloft Gold or equivalent) provides a meaningful amount of warmth - 50g or less of core insulation in our opinion is not sufficient to provide a noticeable effect

- To maintain much of its warmth when wet

- To be highly wind resistant (i.e. not particularly breathable)

- To have a protective hood that shelters the sides of the face

- To pack down small enough to shame a fleece

Not too much to ask? Well perhaps not in 2013, but that was then, this is now.

In 2013 Mountain Equipment released their Compressor Hooded Jacket. Using the best Primaloft ("One", now called "Gold") insulation, with 60g in the body and 40g in the hood and arms. The lightweight, highly wind-resistant Helium 30 outer fabric (which very peculiarly seems to toughen with use) enhances the thermal efficiency of the jacket (since convection accounts for a good deal of heat loss).

The Crux of the Biscuit

In Scramble's opinion the point of an insulated jacket is to stop you getting too cold when you're not active; when you are active, a wind-resistant (non-thermal) outer layer is generally sufficient to keep you warm enough without overheating / sweating. Jackets like the Compressor are fundamentally light belay jackets; static pieces that won't weigh you down but will keep you warm when you stop. We'll get into this later, as current design trends seem to indicate compromised and fuzzy thinking in our view.

Back to the 2014 Compressor:

3 pockets, great zips and a sensible hood

There are two well-sized, zippered hand-warmer pockets and a chest pocket that is quite handy for temporarily storing stuff you'll likely lose to the undergrowth; it will happily hold a smartphone and some snacks.

The hood (and we'll get onto hoods in much more depth later) is pretty good for mountain trekking / helmet-less scrambling purposes, with just enough forward projection to cover the sides of the face (we'd happily sacrifice a little visibility for a few cm more - something like a Buffalo Hood, see below), and an elasticated pull and cinch mechanism on the inside. This requires unzipping the jacket a fraction to access, but once adjusted you can just leave it alone.

If I was predominantly a climber, I'd want more vertical extension in the hood (so it could cover a helmet with a little more ease) and then some form of volume adjustment to prevent it being too cavernous when helmet-less. But for our purposes the hood is more than decent.

It's the 21st Century and zips are not something we can take for granted. The zips on this jacket are the best we've used; they slot into place very easily, glide up and down and never snag. In addition, the front zip is 2-way, so you can unzip from the bottom up or top down - useful for those with harnesses, though not a feature I've had need of to date ... but it's there if I do.

To round things off, there are elasticated cuffs on the wrists and a simple waistband which can be cinched in on either side and holds very well once tightened.

Insulation Layering Versatility

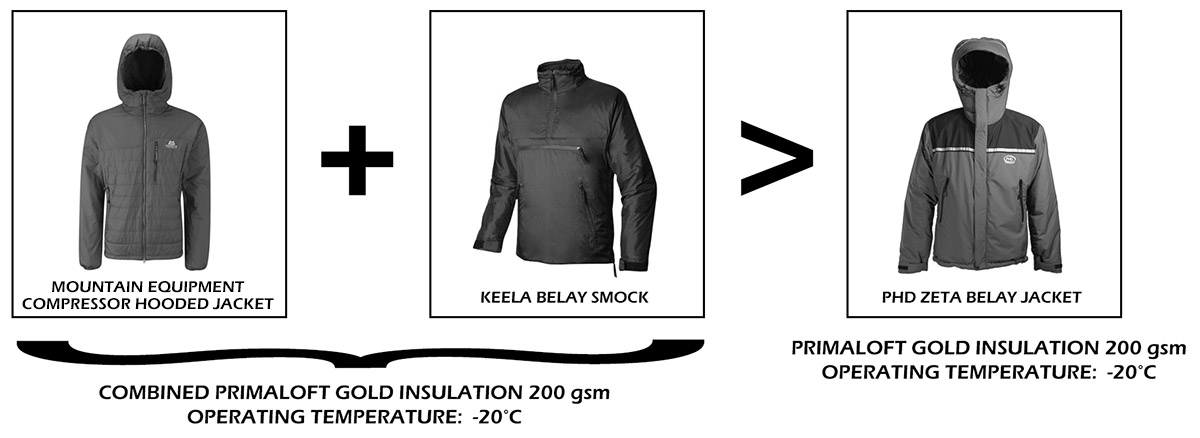

Mountain Equipment's Compressor Jacket on its own will deal with cold summer nights and milder spring and autumnal weather and short (belay / food) stops in freezing conditions. When it drops below -5 / -10℃ (depending on other conditions) we pair the Compressor under Keela's heavier Belay Smock, and this combined (193g Primaloft Gold) core insulation (40g in hood, 173g in arms) provides sufficient warmth around the tent/bivvy in very harsh winter mountain conditions. So ME's Compressor jacket is in action most of the year and only rested over the wintery sides of Spring and Autumn when the Keela Smock takes over.

We use a similar method to our softshell layering, where the lighter internal layer provides the hood. The reasons for this are:

- Insulated hoods are only a necessity in conditions where the jackets are likely paired

- Opting for a lighter hood saves weight (i.e. there's no need to have an additional 133g of hood insulation, which is what you'd have if the Keela Smock had an insulated rather than just a wind-proof hood. More versatile hat combos can do the bulk of the thermal work. What you do want from a hood is protection from wind, precipitation etc.)

- For late Spring, Summer and early Autumn having a light insulated hood means "just-in-case" thermal head gear can be left behind

- A light + midweight jacket combination is very versatile, covering a large range of temperatures down to -20 (possibly lower), and eliminates the need for an extreme option (which may see less use than its price warrants)

Any Negatives?

Only one major negative springs to mind. After pretty much nailing it in 2014, Mountain Equipment did this:

Mountain Equipment's decision to move to an under-the-helmet hood

Mountain Equipment's decision to move to an under-the-helmet hood

We Need To Talk About Hoods

So what's the thinking here? Let's ask Rab ...

Clearly Rab think people will climb in their new Xenon X, since they've changed the insulation to Primaloft Active Gold and have made the jacket more breathable. Yet, their own copy states, the Xenon X is "an extremely versatile piece, perfect for everything from a windy belay at your local crag to spindrift belays high in the mountains". So, it's a light Belay Jacket. More breathable means less wind resistant ... but you want wind resistance in a belay jacket. I'm confused.

In addition, by making the hood under-the-helmet, you have to remove your helmet to take off or put on your jacket. Furthermore, everyone knows that insulation is gained through loft; yet you crush that lofty insulation under a helmet? I'm sure Rab, Mountain Equipment and all the other lycra-banded hood brigade know what they're doing; I'm not sure I get it though. It seems to me that these brands are trying to please everyone. All I can say is, we're not convinced.

What are these Jackets really for?

These jackets, make more sense as lightweight static pieces; something that won't weigh you down but will keep you warm when you stop (whatever it is you're stopping for: belays, breaks etc.). There are other, more efficient moisture trafficking thermal layering options for climbers out there. I wouldn't climb in any of these lightweight belay jackets. You want to be on the cold side of comfortable when active; sweating profusely in a Primaloft masterpiece is not what you want in freezing conditions, since when you stop, that water will suck heat out of your body in quick time; and then you will feel the cold.

So with that said, if these types of jackets are to protect you when you're static, in really harsh conditions, you want to be able to make like a tortoise, and pull your head into its shell. You'll notice with these types of lycra bound hood, the side of the face is completely exposed. There's not really any shell to withdraw into. In fact, this kind of hood is similar to a balaclava, which raises the question, if your hood isn't going over your helmet, why not go hoodless and wear a Polartec balaclava instead?

Certainly, visability is much better with a lycra bound hood, but then visability is improved further with no hood at all. Again, if this is for static use, visability is really a tertiary issue, protection is what we're after.

This is what a protective hood looks like:

Image: Buffalo Systems

Image: Buffalo Systems

Conclusion & Rating

Until someone can come up with a sub-400g jacket, with 60g (or more) of high quality synthetic insulation (Primaloft Gold or equivalent) that packs down small, blocks the wind and features a protective hood .... oh wait, someone did: Mountain Equipment in 2014.

So until someone re-invents Mountain Equipment's 2014 Compressor wheel, we cannot recommend any current lightweight jacket (if you know of one that fits our criteria, please let us know via the form in the footer). What we can say is, if the lycra-bound-non-face-sheltering-under-helmet-design-issue is not a problem for you, then there are a number of ~400g jackets to choose from. Here's a few (in no particular order):

From left to right:

- Rab's Xenon X Hoodie: Probably the best of the bunch while they're still around

- Rab's Xenon X Jacket (2017): Reduced wind resistance (I mean added breathability) and a lost chest pocket later

- Mountain Hardwear's Thermostatic Hooded Jacket: A little too flimsy for our liking

- Alpkit's Katabatic Jacket: A little heavy for our liking

- Mountain Equipment's Compressor Jacket 2015+: More expensive and heavier than Rab's Xenon X Hoodie

- Bergan's Uranostind Insulated Jacket: Doesn't have a hood at all, but ...

... perhaps the future looks something like this:

Bergan's Uranostind Jacket with a Buffalo DP Hood

Bergan's Uranostind Jacket with a Buffalo DP Hood

Sadly, we're only half joking. Let's hope these normally excellent manufacturers can escape this odd bout of group-think; stop copying each other, and instead develop solutions less about compromise and more about clarity of purpose and function.

Product Images (ME's 2014 Compressor Hooded Jacket)

Rating (out of 10)

* The value score is derived from two factors:

1) Competitive Market Price (CMP). This represents our judgement of a competitive online price point if we were to stock the item. e.g. if we feel we would need to sell an item at 40% off (i.e. 60% of its full RRP) to be competitive, then our CMP score will be 6/10.

2) Customer Value Price (CVP). We then make an honest appraisal of the maximum price we would be willing to pay for the item (and we're mean). So if we'd pay 80% of its RRP our CVP score would be 8/10.

We then average the two scores to get our final value score, which in our example would be 7/10.

Last Updated: 13/03/17